India’s electrotech fast-track

Where China built on coal, India is building on sun

Find below a joint report with Sumant Sinha of ReNew, comparing India's progress in electrotech relative to China at equivalent levels of income.

Summary

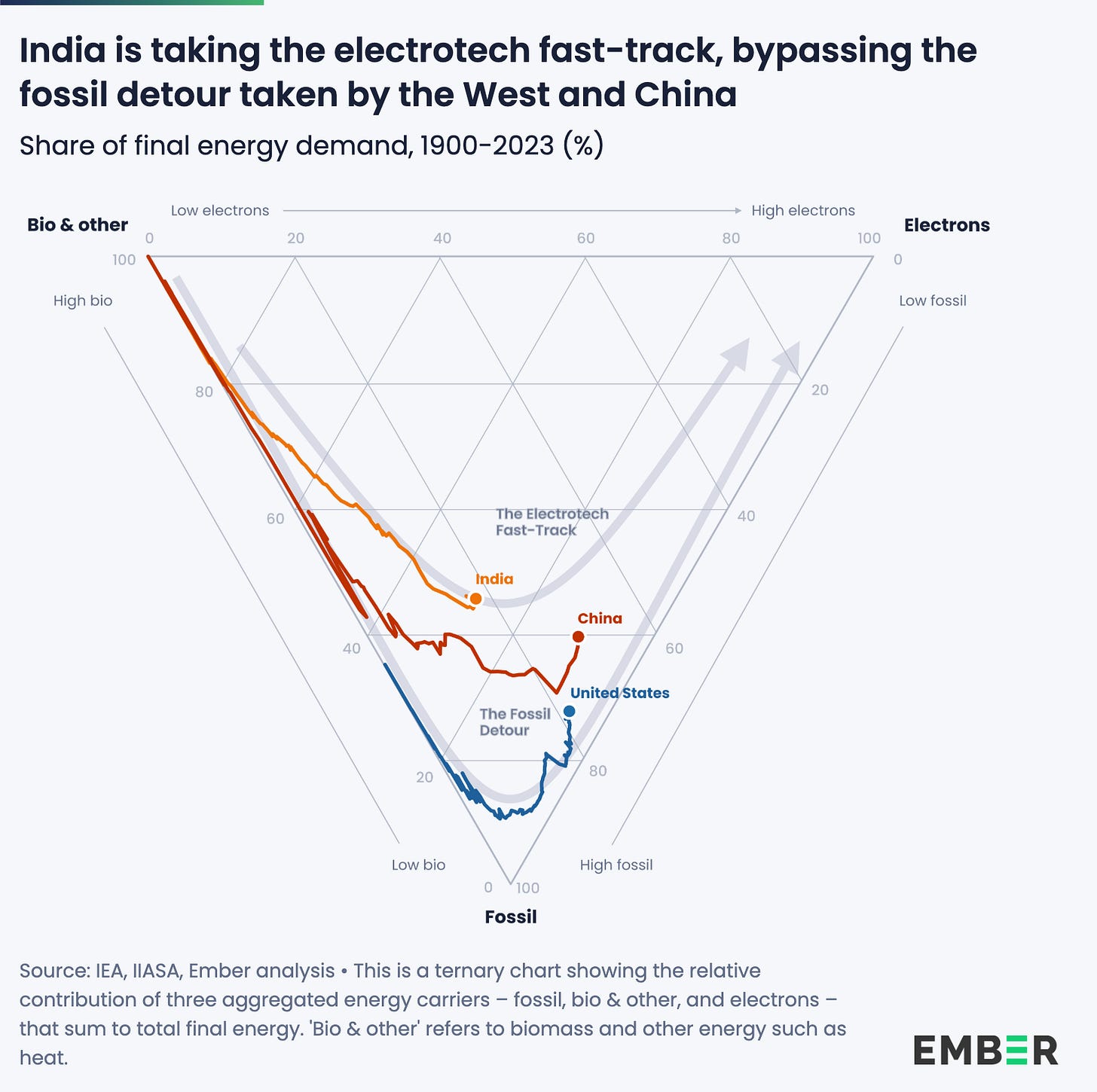

India is forging a better path to the electrotech future of energy. Cheap solar and batteries are enabling India to develop without the long fossil detour taken by the West and China.

When we compare India today with China at equivalent income levels ($11,000 PPP in 2012), several observations emerge:

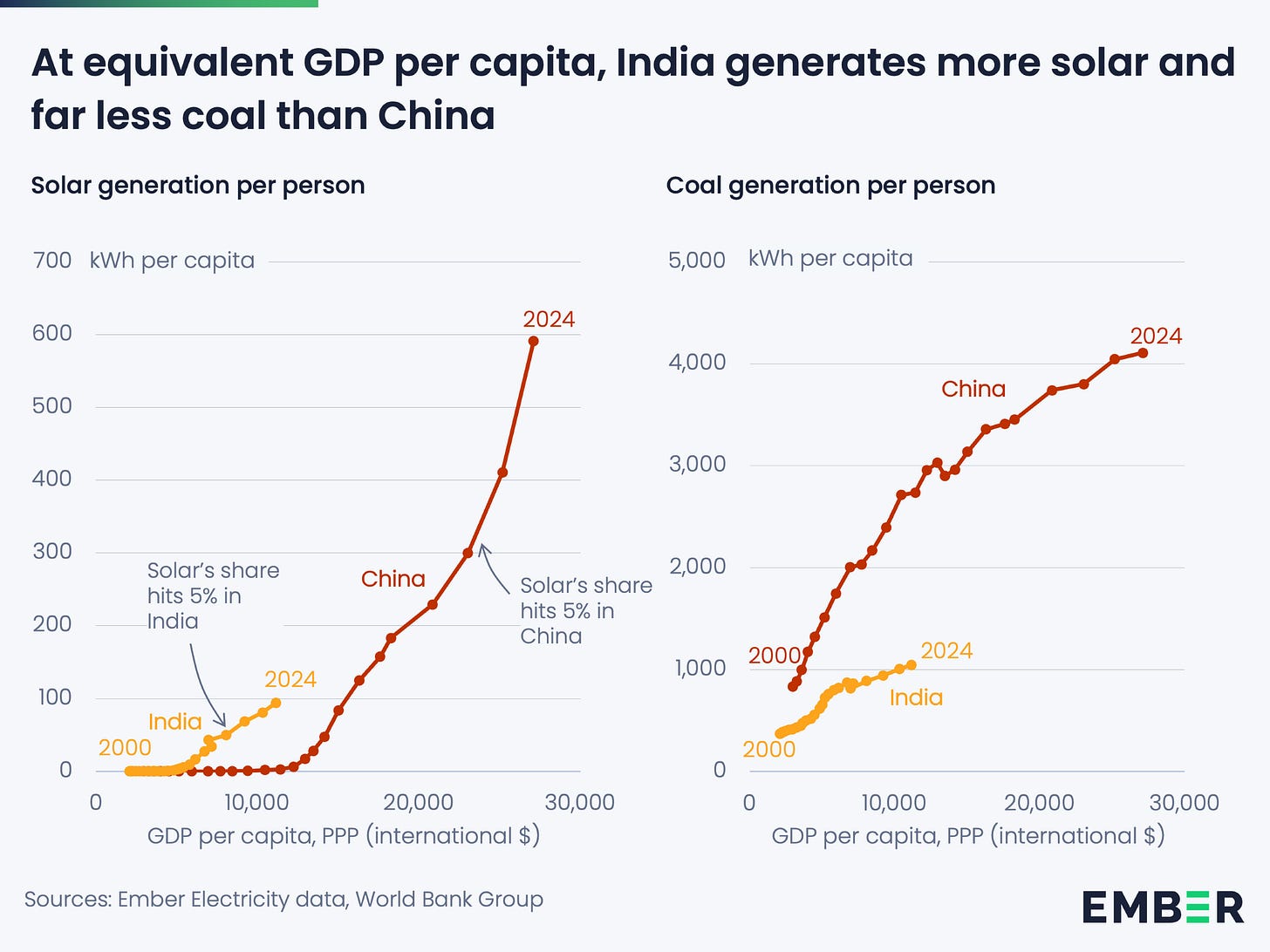

Rapid solar deployment. In 2012, China had negligible solar generation. In 2025, solar accounted for 9% of India’s electricity generation, up from half a percent a decade earlier. India has a powerful new tool to scale cheap power, and it is using it to spectacular effect.

Much lower coal use. Indian per capita coal generation, at 1 MWh, is roughly 40% of China’s level in 2012. Coal demand is approaching its peak and is very unlikely to follow China’s subsequent ramp-up to around 4 MWh per person.

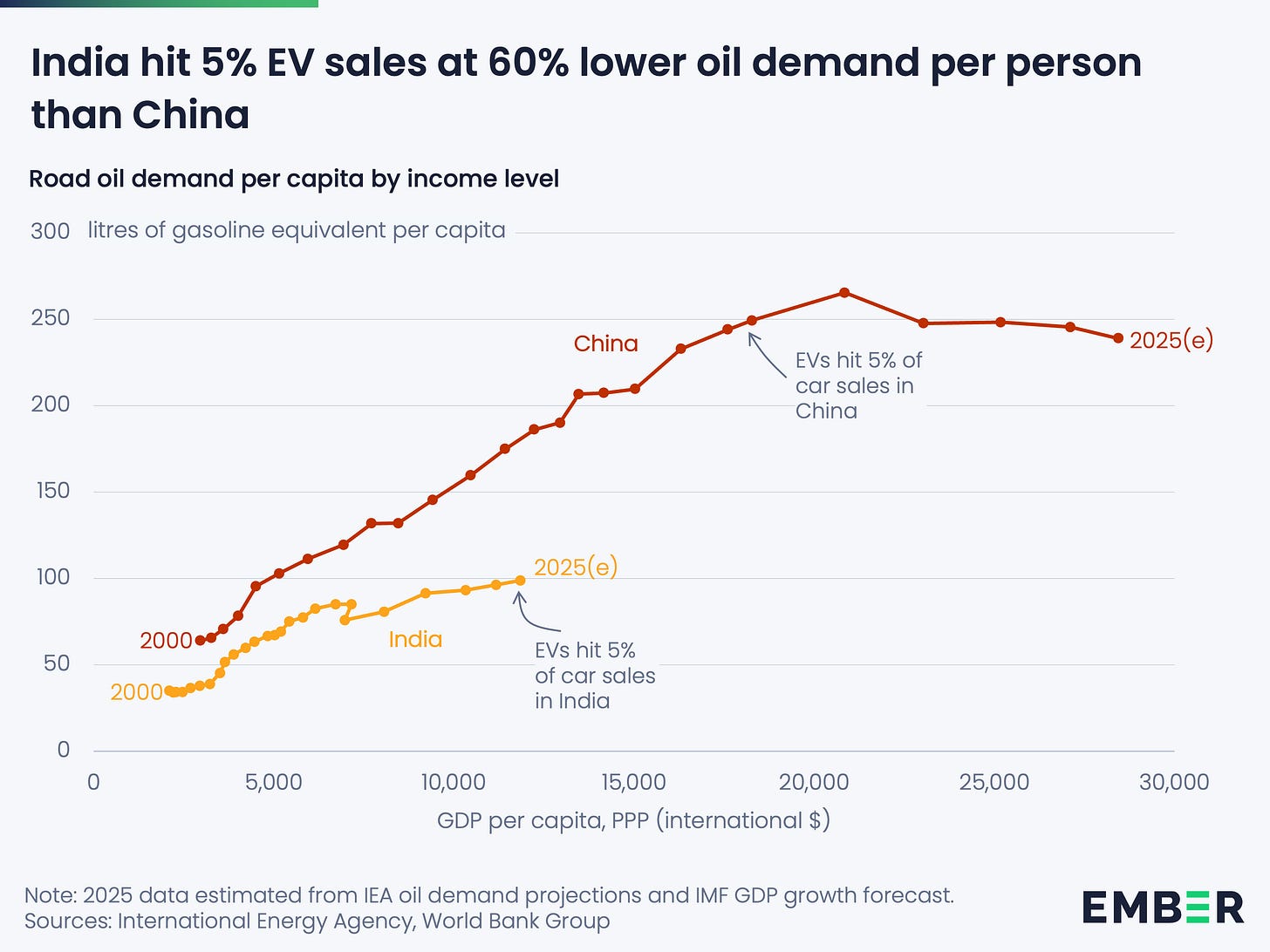

Rapid growth in EVs. In 2012, China had almost no electric vehicles on the road. By mid-2025, EVs accounted for around 5% of car sales in India and the country is the global leader in electric three-wheeler sales.

Much lower oil demand for transport. India’s per capita road oil demand, at 96 litres, is about half of China’s level in 2012 and is close to peaking. India is not going to rescue the oil industry.

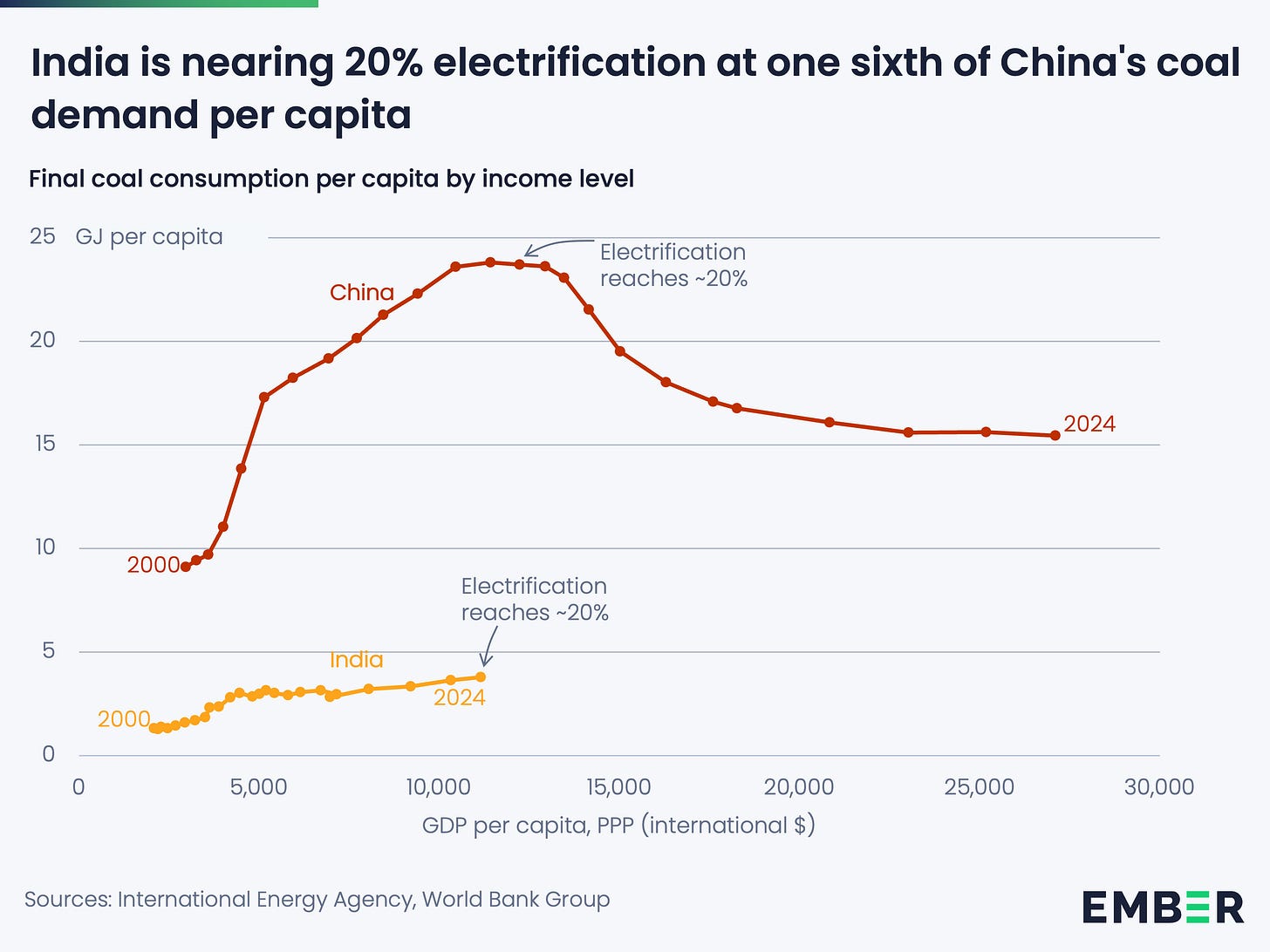

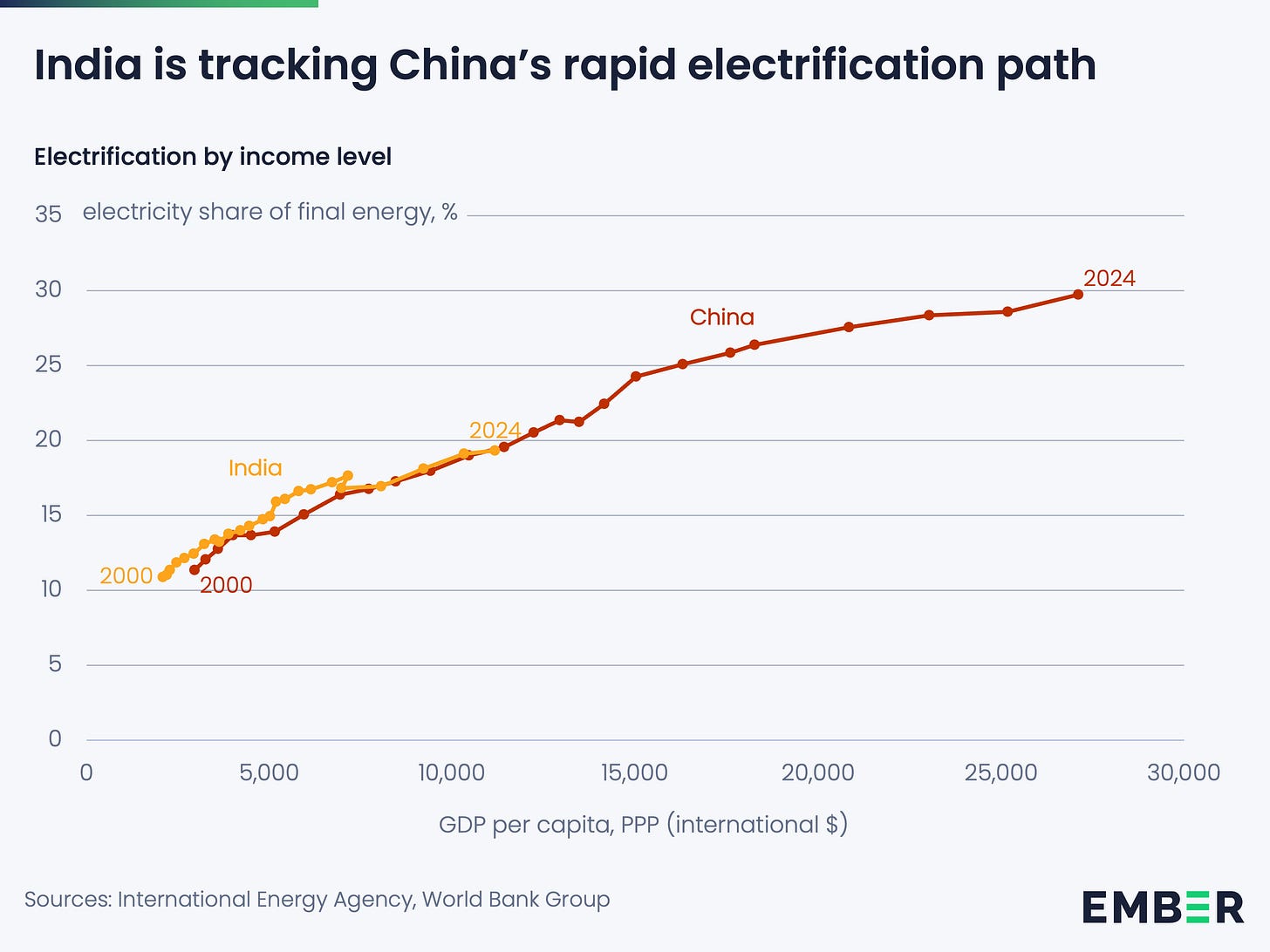

A similar rapid electrification pathway. India’s electrification rate is nearly 20%, comparable to China’s level in 2012, and is growing relentlessly by around five percentage points per decade.

The benefits to India are substantial. This energy path avoids deep fossil fuel dependency while positioning the country to supply electrotech to the world.

A new path for emerging economies. India is showing other countries how to take a cheaper, faster, cleaner pathway to the electrotech future.

Introduction

Many compare India and China’s energy systems as they stand today. From this perspective, China is ahead in most new energy metrics, from solar capacity to electrification.

But the comparison has limits. China is at a later stage of development. China’s GDP in purchasing power terms is over double that of India; its electricity consumption is five times greater; its manufacturing output, in monetary terms, is nearly an order of magnitude larger.

It is more reasonable to compare the two countries at equivalent levels of development. When we do so, a different story emerges. India is generating more solar electricity, burning far fewer fossil fuels and electrifying transport faster than China did at an equivalent GDP per capita.

India is harnessing some of the cheapest solar in the world to power its industrial rise – bypassing an expensive, insecure, fossil-burning interlude. Where China and the West took the long road to the energy future, India is taking a shortcut.

India’s shortcut has consequences, both at home and abroad. It offers a faster, cheaper route to growing electricity. It means greater energy sovereignty at an earlier stage of development. It can position India as a third pole of influence in a world where energy is being reshaped by electrotech and trade by Sino-American competition. Such advantages are not a foregone conclusion, but the signs are promising.

India’s electrotech fast-track

Plummeting costs have opened up new opportunities

Over the last two decades, the cost of core electrotech like EVs, solar panels and batteries have plummeted. To put that in perspective, in 2004, when China crossed 1,500 kWh of electricity use per capita, coal generation was about ten times cheaper than nascent solar photovoltaics (PV). What followed was predictable: over the next decade, coal made up nearly 70% of the growth in China’s electricity generation.

In contrast, as India crosses 1,500 kWh of electricity use per capita, now, solar-plus-storage costs around half as much as new coal plants. This gap is widening as solar and battery costs fall along predictable learning curves, while coal power becomes more expensive with declining utilisation.

Transport tells a similar story. In 2011, when China reached road transport oil demand of 150 litres of gasoline equivalent per capita, batteries were ten times more expensive than they are now, and the electric vehicle industry barely existed.

Meanwhile, India’s road oil demand at 96 litres per capita, is unlikely to ever reach even 150 litres per capita. Electric vehicles are already undercutting internal combustion engines on price. Why pay a premium for foreign oil and local smog?

The implication is that the energy pathway that makes economic sense for India today, as it rapidly industrialises, is not what made sense for China when it made the same journey.

India’s rapid deployment of electrotech

The energy revolution runs along two tracks. First, renewables coupled with battery storage are taking over electricity supply. Second, electricity is taking over energy demand; everything that can economically electrify will go electric, from transport to industry and buildings. On both fronts, India is achieving greater success at earlier stages of development.

Looking at electricity generation first. In India, solar reached 5% of total generation at around $9,000 GDP per capita; in China, it took until about $23,000 to reach that level. Where solar goes, batteries are following fast: the share of renewable tenders paired with battery storage has climbed from about 12% in 2021 to half in 2024.

Meanwhile, coal power growth is fading at levels a quarter of where China’s did. Indian coal-fired generation in 2025 is set to fall year-on-year, though solar’s rise continues uninterrupted. Ember and TERI’s least-cost pathway projects plateauing coal demand through to 2030. Similarly, IEA’s Stated Policies scenario (which has historically underestimated electrotech growth) sees India’s coal demand in 2035 at roughly today’s level. In all likelihood, India will reach $20,000 GDP per capita without coal generation ever exceeding the levels China was burning at $5,000.

Turning next to the competition between electricity and fossil fuels to provide final energy. India is making strides here too. Electricity has reached 20% of final energy at just 4 gigajoules (GJ) of coal per capita, versus 24 GJ when China crossed the same threshold. At a similar level of development, India has reached the same milestone using roughly one-sixth of the coal.

Oil carries greater strategic weight. India is the world’s second-largest net oil importer, behind only China. Half of that demand comes from road transport – a sector rapidly electrifying.

In the race to curb oil imports, India is already far ahead of where China was at the same stage of development. Road transport oil demand per capita is significantly lower, thanks first to smaller, lighter vehicles and now to the rise of electric vehicles (EVs).

Electric cars exceeded 5% of sales in mid-2025, at a point when oil demand per capita is 60% lower than when China crossed the same threshold. In the three-wheeler category, India leads the world, with electric models now approaching 60% of sales. Two-wheelers are following fast: 1.25 million electric two-wheelers were sold in 2024, four times the number in 2020.

A major reason India’s per capita fossil fuel consumption is far lower than China’s at comparable income levels is that India’s growth model is structurally less energy intensive. India generates a third more economic output per unit of energy than China today. India’s cement and steel demand is a fraction of China’s. Unlike China’s heavy, construction-driven development path, India’s economy is lighter and more services-led.

Zoom out to economy-wide electrification. China has long been held up as one of the great electrification success stories of modern economic history, increasing its electricity share of final energy by nearly ten percentage points per decade since 1990. However, align the timelines by GDP per head and India’s progress looks just as impressive.

Several factors explain why India’s electrification rate is tracking China’s. Buildings are more electrified at equivalent stages of development, largely because India’s climate means temperature control is dominated by cooling – which is inherently electric – whereas China’s heating demand is met by a mix of electric and fossil fuels.

Sectoral composition also plays a role: China’s economy, as noted, is more skewed towards heavy industry, which is less electrified. Details notwithstanding, keeping pace with the electrification leader on an income-adjusted basis remains impressive – and an important indicator of competitiveness in an age where electricity powers the highest-value economic activities.

The manufacturing opportunity

Another dimension to the electrotech revolution is manufacturing opportunities. The transition from fossil fuels to electrotech is a transition from extraction to manufacturing – a shift that favours Asia in general and India in particular. If any country has the scale, capital and economic dynamism to become a major electrotech manufacturer alongside China, it is India.

Geopolitics is opening the door further. With Sino-American tensions showing few signs of easing and advanced economies scrambling to diversify their electrotech supply chains, the demand for alternative trading partners is only rising.

There are strong signs India is seizing the opportunity, starting with its electronics industry. India’s electronics industry is surging – nearly sixfold from $22 billion in FY2015 to about $130 billion in FY2025. Domestic mobile phone production alone has risen from 2 million units in 2014 to 300 million a decade later. This matters because, as China has shown, electronics is the gateway to electrotech. The capabilities built for consumer electronics spill over into solar panels, batteries, and EVs. A mobile phone, after all, has more in common with a solar panel than a gas plant does.

Indeed, this momentum is expanding beyond electronics. Solar module production now stands at 120 GW – a twelvefold increase over the past decade, and enough to make India self-sufficient. The shift into upstream components is similarly pronounced: solar cell manufacturing, virtually absent a decade ago, has expanded to 18 GW. Beyond solar, government production incentives are spurring domestic industries for batteries and electrolysers. India is positioning itself to capture a growing share of the global electrotech market.

Green hydrogen offers another example of how low-cost solar is opening new markets. Successive auctions by oil refining and fertiliser companies have resulted in highly competitive price discovery. Bid prices in the range of $4–5 per kg position India among the more cost-competitive geographies globally.

The advantages India’s electrotech fast-track offers

Scaling cheap electricity fast is essential for industrial growth. Here solar has the cost and the speed-to-market advantage: its modularity means it can be installed in months, not the years that coal-based assets need. And because it can be installed at almost any scale, from Mumbai rooftops to Rajasthan desert sun farms, far more actors take part in the energy revolution.

The second advantage of India’s electrotech shortcut is sovereignty. Spending 5% of GDP annually on fossil fuel imports strains the balance of payments, leaves the economy exposed to price shocks and weakens India’s position in a global energy system that is increasingly shaped by geopolitical risks. By taking the fast-track, India can develop with far lower fossil fuel dependency than China has today and enjoy the strategic advantages that entails.

The third opportunity is avoiding legacy costs. There is a considerable benefit to building the new when you have less of the old. In India, the total cost of solar projects already undercuts the marginal cost of running existing coal plants. Ember estimates that by 2031, over a third of India’s installed coal capacity could be operating at under 40% utilisation, undermining its economic case. But the assets at risk are far smaller than China’s. As China faces the painful task of writing down its coal fleet, India can emerge with far fewer scars.

Overall, India is on a very different development pathway from China, industrialising on modern renewables, put to work through electrification. Leaning into this offers multiple advantages: manufacturing opportunities, energy sovereignty and faster scaling of electricity supply. As the fastest-growing major economy and the world’s most populous nation, India’s choices carry powerful demonstration effects. It is showing other emerging economies that electrotech can power industrial growth, not just follow it.

The most important thing to note here is that despite China and India having similar GDP per capita initially, India opened up its economy in 1991, which was 13 years after China did in 1978. The result is that India’s GDP per capita PPP today is where China’s was 13 years ago, at least according to the IMF. This means that if current trends continue, 13 years from now India’s GDP per capita PPP will be where China’s is today. Given how different India’s development model has been, it’ll be really interesting to see how this would transpire in the next decade and a half.

Thank you; this is helpful. A few thoughts and questions.

1 Comparisons between China and India are hard to interpret because China does so much of the world's manufacturing, which I guess India is never likely to do. So I wonder what your charts would look like if they were done on the basis of some kind of relationships between energy and consumption rather than production?

2 Do you know what oil, gas and coal demand India expects to be coherent with the goal of a self reliant and prosperous economy by 2047?

3 I looked at the Coal India accounts the other day - and was surprised by how profitable the business is. I didn't do a deep enough dive to be completely sure - but it looked like the government gets £6-8bn from it each year. Should we worry about this. (a) as its so profitable, the cost of India's own coal could come down quite a lot to compete with non fossil fuel electricity and (b) the government has a strong interest to protect it.