Silos for Sunshine

We’ve mastered harvesting the sun, but storage is the gamechanger

Hi all,

The Financial Times recently published an excellent long read on batteries, in which Daan was quoted comparing the rise of batteries to earlier breakthroughs in storage such as grain silos and refrigeration.

There’s more behind that thinking — in this note we expand on the idea.

The shift to renewables represents an agricultural revolution for energy, moving from searching and extracting scarce fuels to harvesting abundant sunlight in place. Much as granaries and refrigeration transformed food markets, storage will turn electricity from perishable to persistent, unlocking a new era of energy abundance.

Summary

A new kind of harvest. The world is in the midst of a renewables boom akin to the agricultural revolution; moving from foraging scarce fossil fuels to farming abundant sunlight in place.

Storage is the key to this new revolution. From grain silos to refrigeration, every storage breakthrough has turned the perishable into the persistent; renewable electricity can now follow the same pattern.

Storage uptake will likely exceed forecasts. Like fridges and silos before it, cheap batteries will be deployed along the supply chain to provide resilience and convenience. The result could be a market three to six times larger than conventional cost-minimising forecasts predict.

More storage means less transport. Before refrigeration, milk and fish had to reach markets daily, requiring vast rail networks for peak morning demand. Cold storage ended that rush. Likewise, batteries will curb the need to overbuild grids to get renewable supply to demand centres as power can flow off-peak.

Storage will rewire the market. Once refrigeration became widespread, daily market visits gave way to weekly supermarket trips. Electricity will follow suit: as storage grows, power trading will shift from hourly spot-trades to daily or even weekly markets. This new rhythm will require market redesign.

A self-reinforcing battery boom

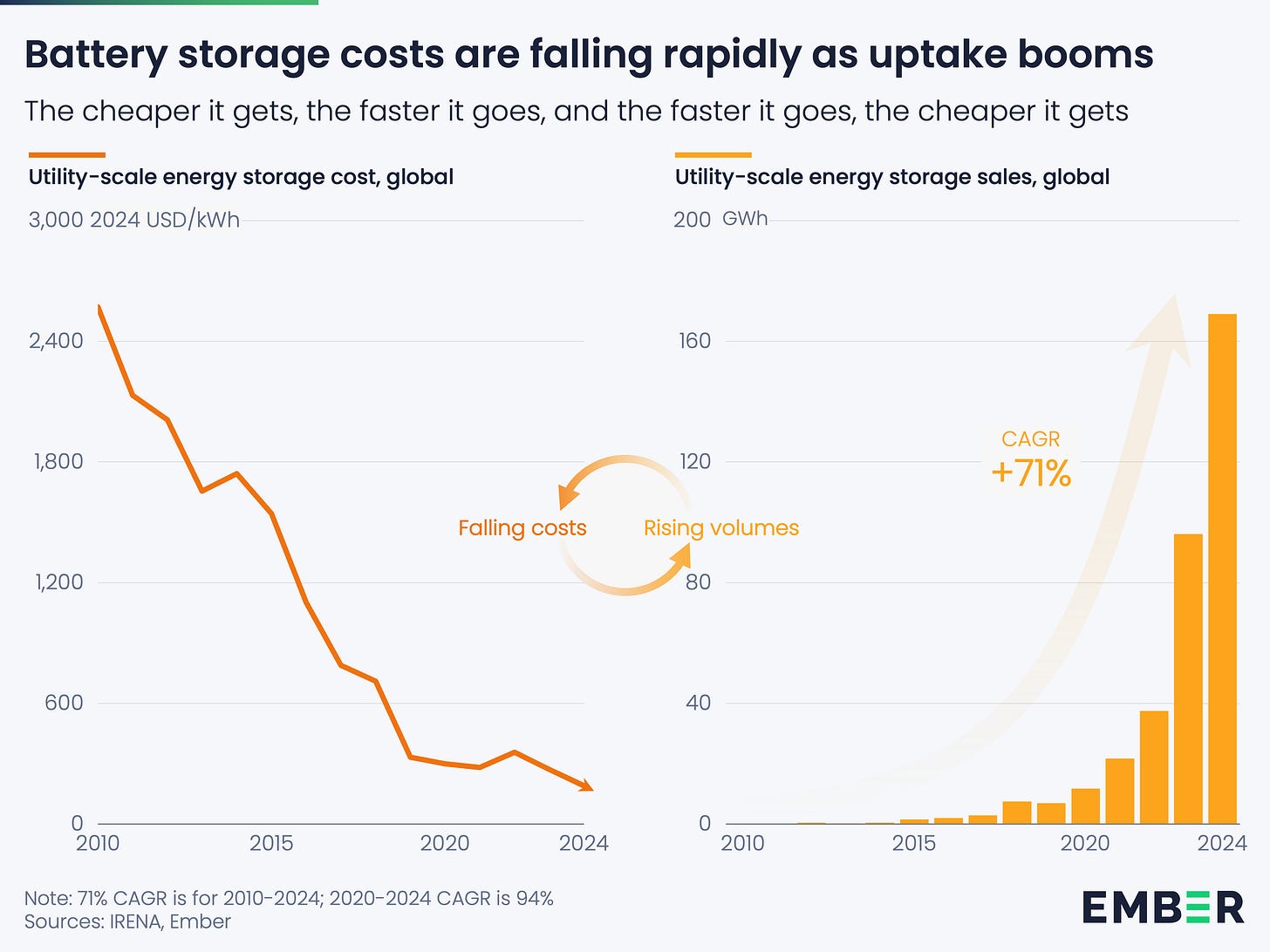

We are in the midst of an electricity storage boom, with deployment nearly doubling every year. In 2024, developers deployed over 160 gigawatt-hours of new battery storage, which is nearly as much in one year as in all recorded history. As deployment scales, costs continue to fall; by as much as 40% last year. Recent tender results from China show turnkey costs for stationary storage around $60 per kilowatt-hour, with similar prices in India and Saudi Arabia, indicating prices continue to fall aggressively in 2025. That marks an order-of-magnitude drop compared with typical battery prices just seven years ago.

Battery storage quality has improved dramatically as well — with near “plug-and-play” grid systems cutting installation time and cost, longer lifetimes (some warrantied for as much as 20 years), minimal fire risk, and the rise of sodium-ion batteries that use no critical minerals.

A virtuous cycle has taken hold: lower costs lead to faster deployment, which in turn drives further cost reductions through learning and economies of scale.

This rapid progress has sparked a debate about how big storage could — or should — become. Many still seem to treat electricity storage as a completely novel challenge. It isn’t. The basic problem of how to store a valuable but perishable resource is one humanity has solved many times before.

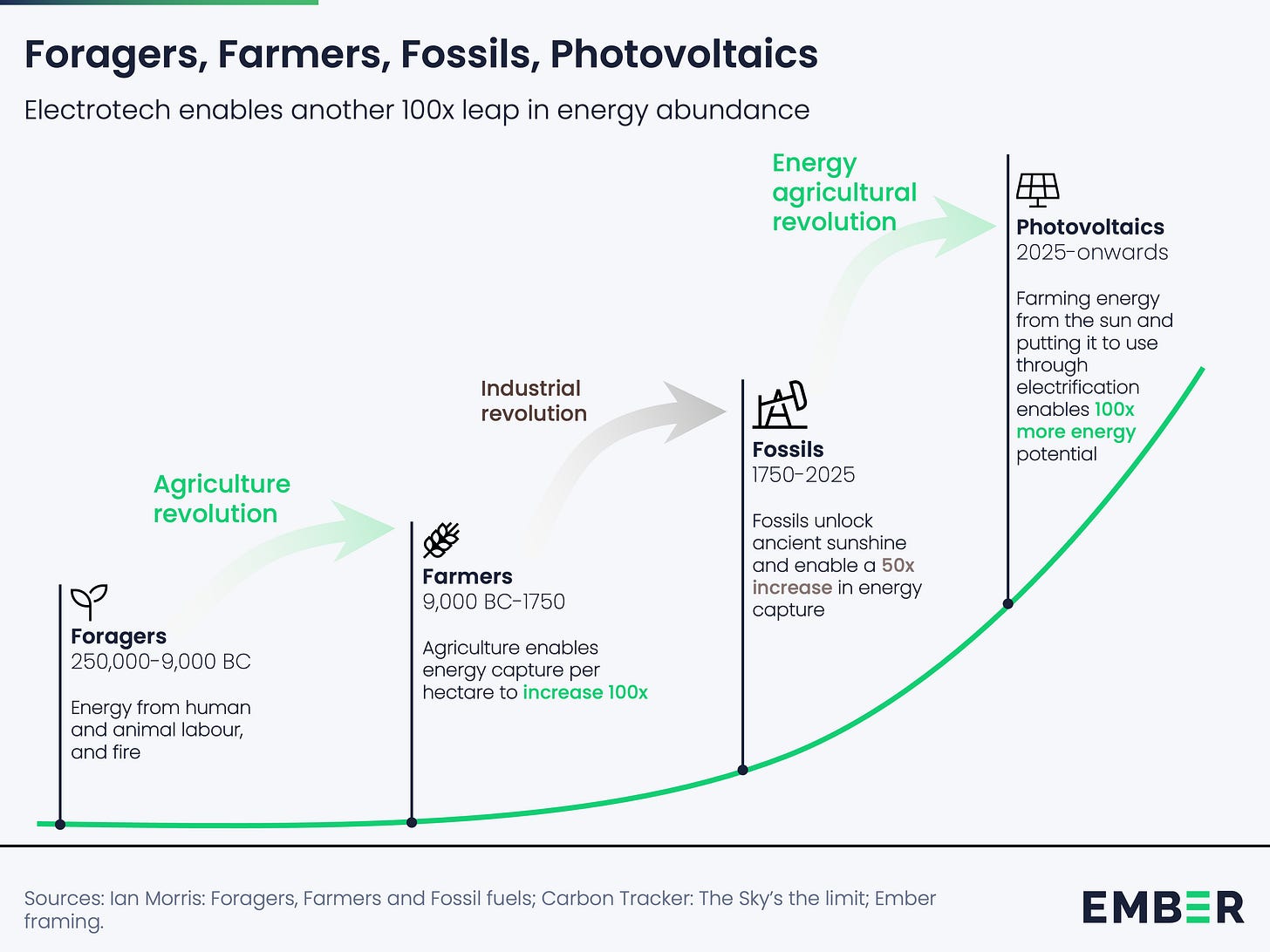

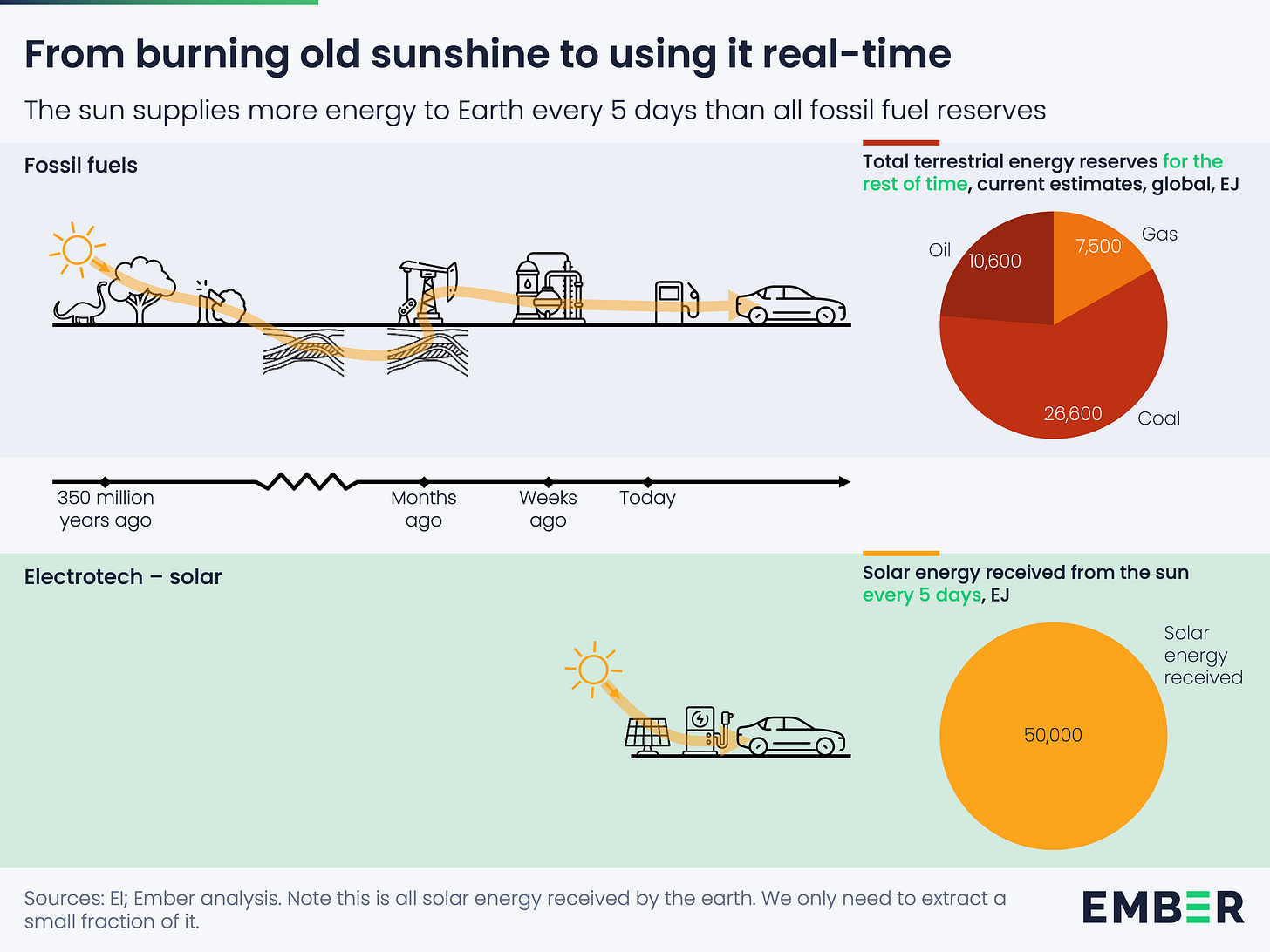

The energy agricultural revolution

The shift to renewable energy is more than a technical upgrade; it marks a structural change in how societies generate and use energy. We call it the electrotech revolution. For centuries, humans have scoured the planet for fossil fuels, chasing energy across continents. Now we are learning to harvest it in place, from sunlight and wind, reliably and close to home.

There is a clear parallel with the agricultural revolution here. When early societies learned to farm, they began producing food in place — harvesting from the same fields again and again instead of chasing animals across vast territories. That shift unlocked far greater energy yields from the land, rising by roughly two orders of magnitude in most estimates. The result was abundance, settlement, and growth: the foundation of civilisation itself.

An analogous revolution is now underway in energy. By shifting from tracking down and collecting fossil fuels to farming sunshine, wind, water and heat from the ground, we are unlocking a resource base that is more local, steady and vastly larger: capable of supplying orders of magnitude more energy than fossil fuels — with every nation sitting atop renewable resources at least ten times, and for some a thousand times, greater than its demand. As renewable generation scales and electrification carries it through the economy, the age of electrotech marks a new period of energy abundance.

Key unlock for an agriculture revolution: storage

As the energy sector enters its own agricultural revolution, it faces a familiar challenge: how to plan for variable yields and preserve abundance through leaner periods.

Agriculture has always produced perishable goods, and storage has long been the key to transforming volatility into stability. Humanity has grappled with this problem for a very long time; in fact, it lies at the foundation of civilisation itself. More than 10,000 years ago, early societies began building granaries to hold surplus grain through leaner seasons; allowing for settlement and trade.

For millennia afterwards, inadequate storage forced farmers to sell harvests immediately, creating recurring cycles of glut and scarcity. Across global breadbaskets, grain and cereal prices collapsed at harvest and surged months later. Lacking reliable storage, farmers rushed goods to market, overloading transport routes such as shipping and rail networks. Only more advanced storage solutions that emerged in the late 19th and early 20th century stabilised the market.

The same logic now applies to renewable electricity. Electricity is the ultimate perishable good; more so than grain, milk, or fruit, as it must be consumed within a fraction of a second. Producers race their output to market — literally at the speed of light — along copper wires, often oversupplying the system and driving curtailment and extreme price swings.

The rise of new electricity storage tech such as batteries addresses much of this challenge, just as previous storage technologies did. Grain silos stabilised harvests; refrigeration globalised fresh food. In every case, storage moved from rare and costly to cheap and ubiquitous. Electricity storage follows the same trajectory, turning the perishable into the persistent.

Comparing this revolution to earlier ones offers useful perspectives for a market still finding its shape. From this historic perspective, four broad takes emerge.

Take 1: Storage will probably be (much) bigger than we think

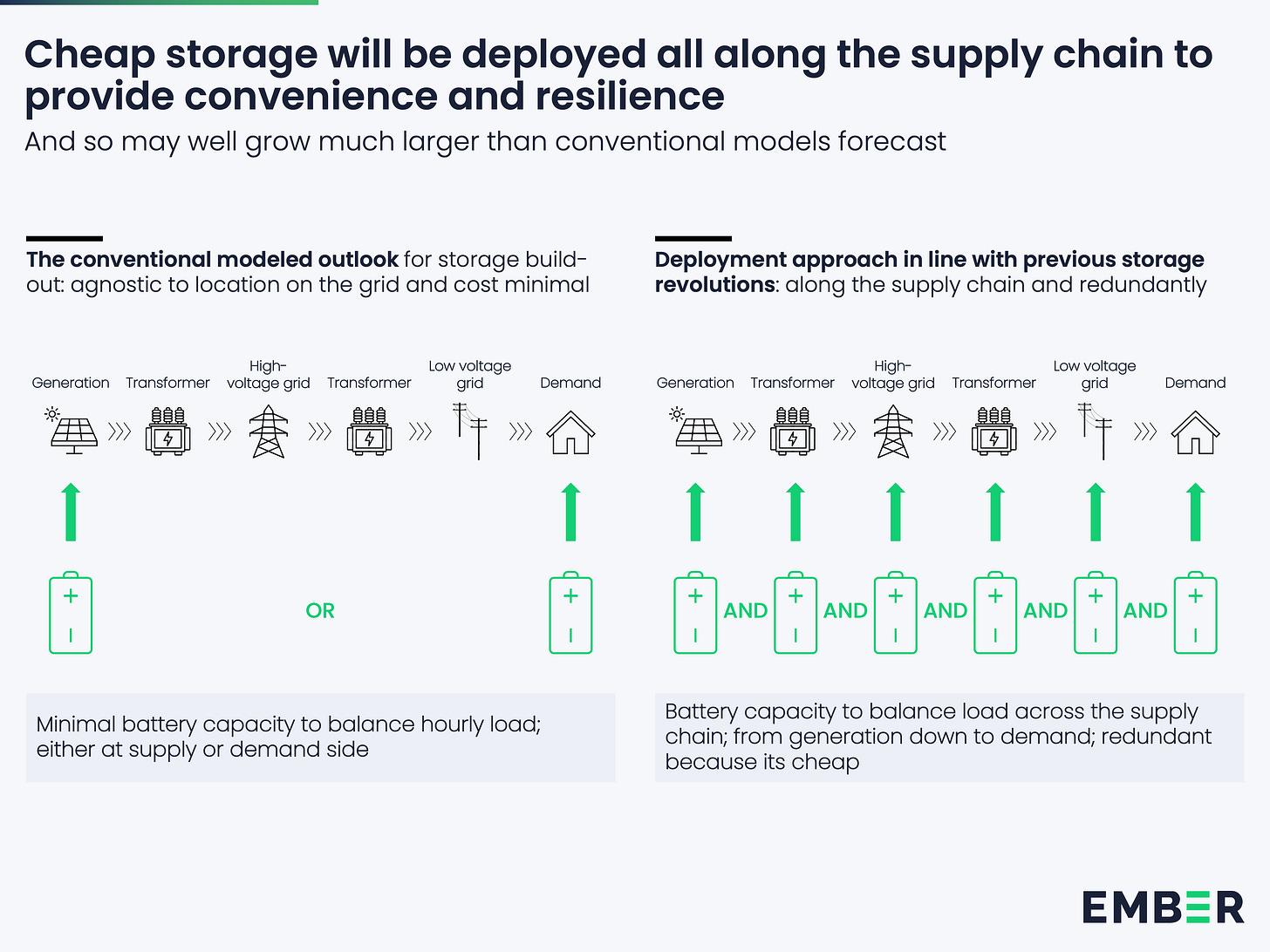

Seen through the lens of past storage revolutions, one thing becomes clear: forecasts almost certainly underestimate how large electricity storage will become. Most energy outlooks tend to only model the bare minimum needed to balance grids; typically 30–40 TWh globally in the long term. But this ignores two powerful forces: resilience and convenience.

No one ever calculated the cost optimal minimum size of fridge storage space the world required. Once refrigeration became affordable, businesses and households began purchasing their own units for greater flexibility and peace of mind, installing them throughout the supply chain — from farms and distribution centres to supermarkets and homes. The same logic will apply to batteries. As costs fall, they’ll appear everywhere: at solar farms, substations, businesses, and homes — not just where they’re strictly “needed.”

We may even put small batteries in most electrical appliances, from laundry machines to lightbulbs and cooktops — the “batterisation of everything” as energy analyst Gerard Reid calls it. If each device can run independently for a while, homes could smooth their own demand at an outlet-to-outlet level in real time, balancing loads not just across the grid but within the house itself.

Rough assumptions suggest how quickly this could scale. If utilities pair each kilowatt of solar with one or two kilowatt-hours of storage, grid operators install a few hours of storage at each substation, homeowners keep 20–30 kWh systems, and factories maintain a few dozen MWh for backup, the totals add up fast. Across roughly 20 TW solar, 500,000 substations, 3 billion households, and a million large factories, that comes to around 100–180 TWh of stationary storage globally in the long term— three to six times higher than current long-term forecasts. The manufacturing capacity to support this is already being put in place: global battery production is on track to reach twice even the most ambitious (net zero) IEA forecasts by 2030.

As with every previous storage revolution, the end state won’t be a bare-minimum system. It will reflect how people actually live: with buffers, redundancy, and a preference for autonomy.

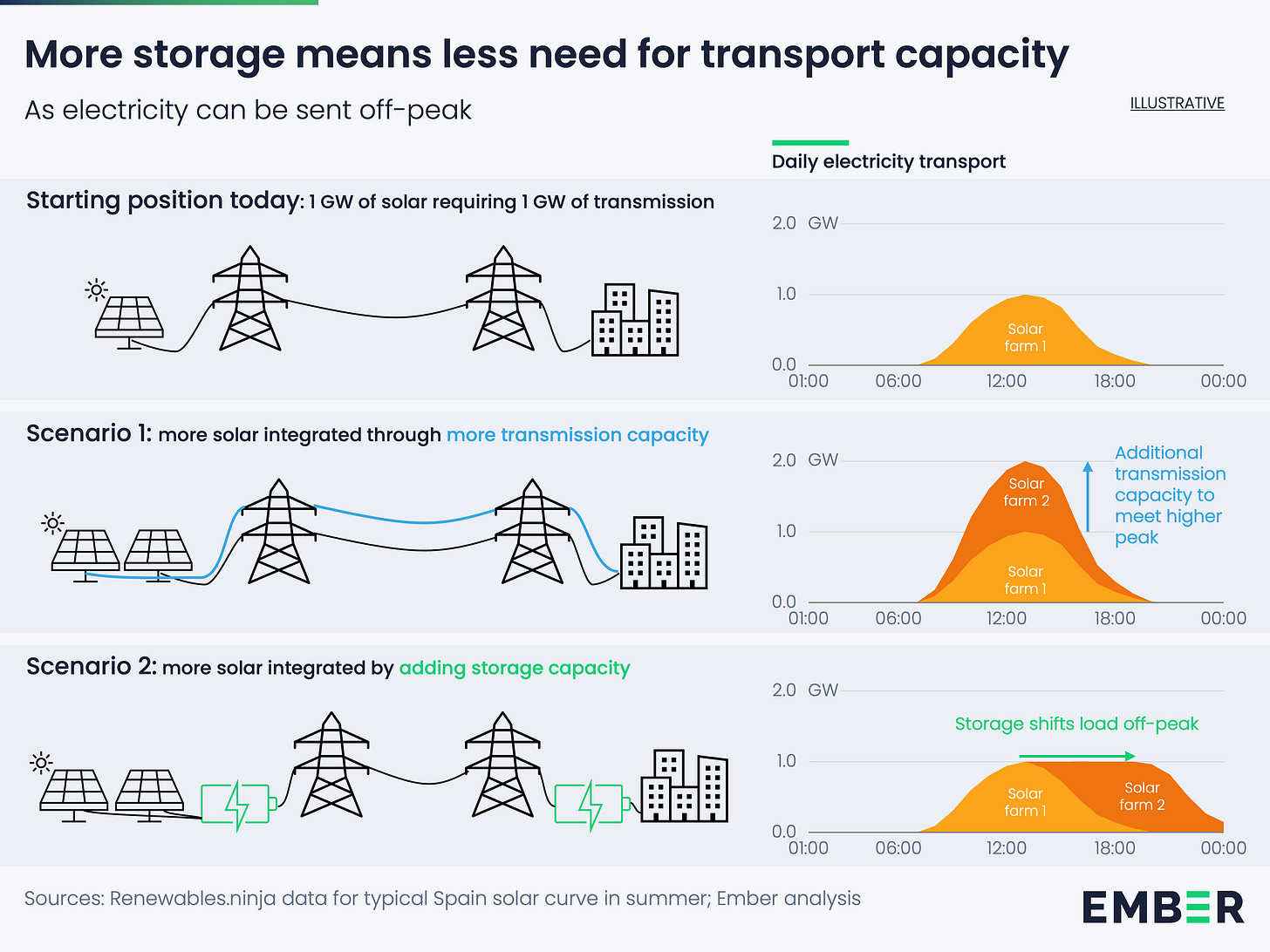

Take 2: More storage means less transport

One overlooked consequence of storage revolutions is their impact on transport. Before refrigeration, fresh food had to reach markets every day, making supply chains fragile and inefficient. Cold storage changed that. Express “milk trains” once raced into cities like New York every morning to deliver dairy products before they spoiled, driving the construction of new rail lines built to handle that daily rush. When refrigeration spread, goods could be stored near supply centres and demand centres and shipped off-peak. The need for peak transport capacity fell, and much of that overbuilt network was gradually abandoned or repurposed.

Electricity is following a similar path. Today’s grid depends on long-distance transmission because supply needs to meet demand instantly or is lost. That means we build transport capacity to meet the highest peak loads, even though they occur for only a few hours per day or even per year. As storage expands, that urgency fades. Power can move in time, not just in space. Batteries, like cold storage a century ago, smooth the system; storing energy wherever it’s convenient, and allowing transport to spread into off-peak times.

Many grid plans still lag behind this reality. Much of today’s strategy assumes the old race to market: ever more transmission to chase supply in real time. Cheap batteries support a different model of a more distributed system where storage can often substitute for costly grid upgrades. Ignoring this is like building new rail lines in the 1920s to rush dairy products to New York while overlooking the arrival of refrigeration.

Local storage doesn’t just flatten peaks or defer investments; it also adds resilience to transport interruptions. Communities with their own batteries can ride through outages, much as towns with granaries once endured a failed harvest or an interrupted supply line.

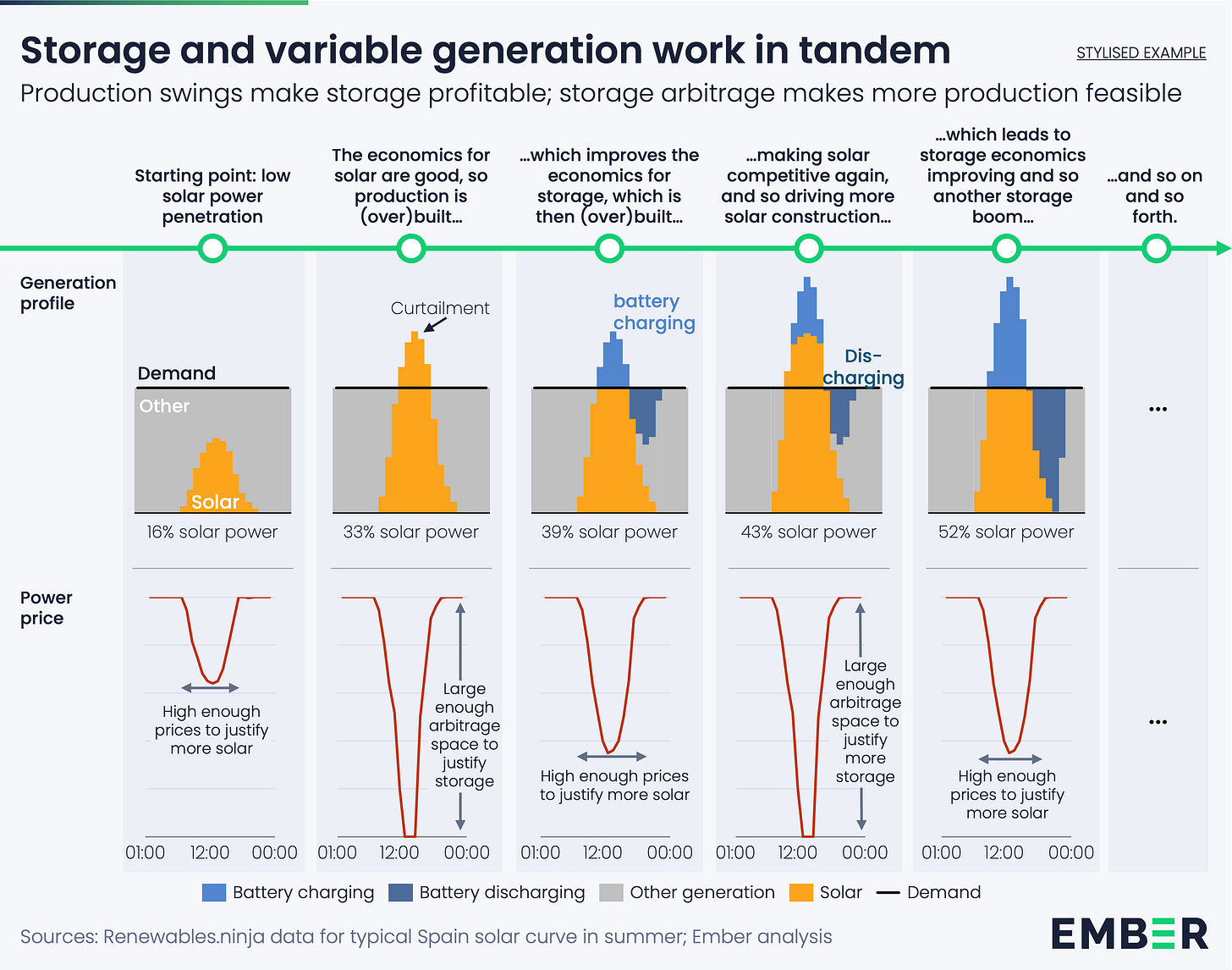

Take 3: Storage and production help each other

A common critique of the storage boom is that it can’t last; that storage destroys its own market. The more storage you build, the less prices fluctuate, and the less profitable each storage project becomes. The same is said of solar: the more panels you install, the more oversupply and low prices you get when the sun is shining, and so the lower the revenues for all solar farms. Both arguments make sense in isolation, but together they don’t.

Storage and variable generation obey different economics. Production thrives on price stability; storage profits from volatility. That makes them natural complements.

The food storage analogy makes this easy to see. From the granaries of ancient Egypt to the imperial storehouses of China, societies have long used storage to tame production volatility. The 19th-century American Midwest offers a more recent illustration: as grain silos spread, farmers could hold back their crops rather than flooding the market at harvest, stabilising prices and improving profits. Stability made farming more attractive, drawing investment and expansion — which in turn made more storage worthwhile. Storage and production complemented each other to enable the Midwest’s grain and cereal boom.

The same feedback loop now shapes electricity. When solar expands, midday prices collapse, creating the arbitrage space that makes batteries profitable. Once built, those batteries flatten prices again, allowing even more solar to follow. Meanwhile, solar and batteries themselves continue to get cheaper as they scale, meaning they can thrive under progressively lower prices and thinner arbitrage opportunities. Storage and generation climb together; each expansion justifying the next. Just looking at storage or production economics in isolation seems to suggest cannibalisation; but in reality it is coordination between variable supply and storage.

Take 4: Storage will reset market dynamics

Many of today’s electricity markets trade in hourly and 15-minute intervals. That structure exists not due to preference but by necessity — supply and demand must match instantly because storage has long been scarce. As storage expands, that constraint will ease, and markets will evolve much as they did for other perishable goods.

Perishables like milk once had to be sold daily in market squares or delivered door-to-door for same-day consumption before they spoiled. Then cold storage came in which let shops and households stock food for days and weeks, turning daily markets into weekly shopping trips. Storage reset the cadence of the market from day-to-day to week-to-week.

Electricity will likely follow the same path. Once power can be stored for a few hours, trading shifts from minute-to-minute scarcity to buying the cheapest energy within that few-hour window. As storage grows, that time window — and with it, the structure of the market — widens. Markets that once cleared every hour will clear across days or even weeks instead, with prices reflecting time-shifting rather than instant balancing.

Emerging long-duration energy storage (LDES) technologies will extend that logic further, much like freezing extends the life of food far beyond cooling. As LDES scales, the entire shape of the market can change from fast-cycling spot trades to slower, deeper cycles of accumulation and release, resembling today’s gas or grain markets more than the electricity systems of the past.

The path to energy abundance is paved with storage

We are entering an era of energy abundance. The sun delivers more energy to Earth every five days than all known fossil fuel reserves combined. As we shift from using fossilised sunlight to real-time solar power, the challenge is no longer energy capture, but energy storage.

Humanity has solved this challenge many times before with other perishable goods. Storing renewable electricity is but the latest challenge in a long line of storage revolutions. As batteries and other solutions get cheaper, they’ll spread across homes, grids, and devices; not just to balance supply and demand, but to deliver resilience and convenience.

We’ll need to plan for this; integrating storage not as an afterthought but as a core part of how we build grids, design buildings and products, and organise power markets.

Renewable electricity may be a new kind of harvest, but the challenge of storing it, and the system-wide shifts it sets in motion, go back to the dawn of agriculture. The technologies may be new, but the dynamics are as old as civilisation.

The revolution is going to be paradigm shifting. The evolution of storage should eliminate the need for transmission. At the individual home level storage for 2-3 days consumption will soon become affordable and the energy itself is free. If there continues to be a need for transmission, it could become the reverse of what it is now as excess home generation could be injected into the system powering residential or businesses unable to self generate enough for their needs.

The work you do is amazing.